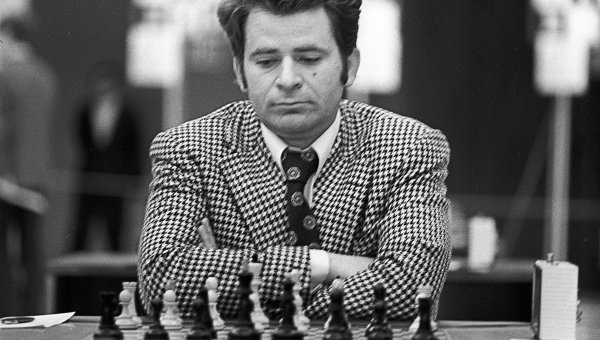

Continuing with the recent anniversary theme, today we acknowledge a recent significant birthday for one of the game’s true titans.

The 10th Chess World Champion, Boris Spassky celebrated his 75th birthday on the 30th of January. I’m not going to regurgitate his wonderous achievements or indulge in any sentimental recollections about the ‘good old days’ here – well, not much anyway! There are plenty of folks out there better qualified to do that than I. Chessbase being just one example.

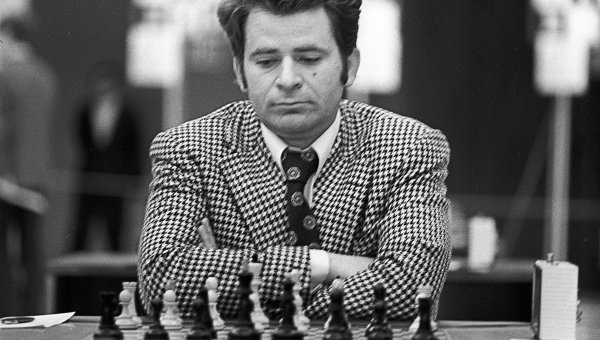

Boris was disappointed to see that, once again, his wife had ordered a chessboard-shaped birthday cake with pieces for candles

What I will say is that I’ve always had a bit of a soft spot for Spassky and my feelings were reinforced when I saw the recent celluloid about Bobby Fischer. It seemed to me that Fischer was able to complete his match with Spassky in ’72 due in no small part to the Russian’s patience, generosity and sportsmanship. Spassky wanted to play that match and he put up with Fischer’s shenanigans despite the fact that they undoubtedly had an adverse effect on his psychological equilibrium and therefore his playing standard.

I could re-publish any number of Spassky’s great masterpieces. The one against Bronstein (Leningrad 1960) or the one against Larsen (Belgrade 1970) are the ones that most readily spring to mind and get trotted out whenever his masterpieces are considered. However, I’ll resist the temptation in order to bring you a less prominent encounter that may have escaped your attention.

Spassky’s 16th move of the first game in viewer at the bottom of this post was adjudged by Tim Krabbé to be the most fantastic of all “The 110 Most Fantastic Moves Ever Played” back in 1998. The game was played in the 1959 Russian Championship play-off in which Spassky and his opponent, Yuri Averbakh were competing with Mark Taimanov. I’ve put the whole game into the viewer but move 16 is the point at which Spassky (playing Black), after sadly reflecting on the misery of his situation, decided that 16…Nc6! was required. On his website Krabbé annotates this move as follows:

About his #1 greatest move, Spassky wrote to me: I have played 16…Nc6 because I did not see any other practical resources because my position was so passive. I was very surprised that Yuri Averbakh was thinking about 1 hour (!!) (55 min.) I considered that after 17.dxc6 bxc6 18.h6! Bh8 White would have two pieces up and they could manage the win very easy. Mark Taimanov: “I would rather resign the game than to make such a move…

It would be greatly amiss of me not to add that Spassky’s opponent in this game, Yuri Averbakh, was 90 on the 6th of February! I believe he is currently the oldest living Grandmaster. Chessbase also has a nice tribute and interview with him on their website.

To end this appreciation I would like to set straight a record that was recently made public by Vladimir Kramnik. I was listening to the Full English Breakfast podcast last week in which Macauley Peterson interviewed Vlad right after his win in the London Chess Classic. At one point in the interview Kramnik was talking about living in Paris (were Spassky also resides) and the fact that he hadn’t yet learnt French. He recounted thisanecdote about his illustrious countryman.

He’s been living in France since ’73 or’74 and actually his French is still not great. Once I visited him at his place and he had a big sign on the door of his bureau cabinet in Russian which was saying ‘Learn French idiot!’

— Vladimir Kramnik interviewed by Macauley Peterson for the FEB

Readers may think nothing of this apparently amusing story but, in yet another exclusive for this website, I can now reveal the true and rather more poignant origin of that handwritten note. At the beginning of last week I was alerted to the Kramnik interview by our erstwhile guest columnist, Lady Cynthia Blunderboro, who sent me this e-mail.

Dear Intermezzo,

Perhaps you will have come across the recent interview of Vladimir Kramnik by the chaps at the Full English Breakfast. In it he mentions a note stuck to Boris Spassky’s bureau cabinet that he naively assumes must have been written by Spassky himself and refers to his failure to learn the language of his nation of residence.

Setting the record straight, Lady Cynthia Blunderboro

I say “naïve” because Kramnik clearer failed to consider some plain facts which point to the true origin and nature of the note, which I should add, I witnessed being written with my own eyes.

First of all, the note is, as I mentioned above, handwritten and if Kramnik had given it any more than a perfunctory glance he could not have failed to notice that the handwriting was not Spassky’s. Secondly, if he had taken a further moment to inspect the note he wouldn’t have missed the familiar size and stock of the paper which is clearly a score sheet from a chess game. Finally, if he had been minded to consider a potential alternate meaning for the three words in the note he might have deduced that the word “French” could in fact refer to the chess opening of that name and not the language.

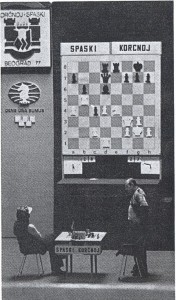

The tragic truth behind that note must cause poor Spassky to suffer a pang of anguish every time he reads it. In 1977 he had qualified to play in the final Candidates Match of the World Championship cycle against Viktor Korchnoi, for the right to play Karpov. The match was played in Belgrade just a year after Korchnoi had defected from the Soviet Union. The bad blood between Viktor and the Soviet bureaucracy was just beginning. In fact some of the antics and psychological chicanery that distinguished the subsequent World title matches between Karpov and Korchnoi originated from the acrimonious dénouement of this Belgrade encounter.

The match started very badly for Boris who went five games behind. The main instrument of his agonies was Korchnoi’s use of the French Defence which Spassky for some reason found very challenging to overcome. In seven games across the match where Korchnoi played the French Spassky managed a score of only +1, =2, -4. Desperate for a break, in game 10 Spassky suddenly decided to consider his moves in his designated “relaxation box”, using a large demonstration board to analyze his moves. He would only go to the board to play his moves, record them and press the clock and then return to his box. This tactic drew a protest from Korchnoi, but he was clearly unnerved and Spassky fought his way back almost to equality in the match winning games 11, 12, 13 and 14 by which time Korchnoi had begun mimicing Spassky’s behaviour to no avail.

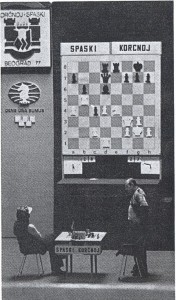

Belgrade 1977. Spassky is the one in the sun visor!

The match descended into farce and relations between the two men had become very poor. By the time they played the 17th game Spassky had returned to consider his moves at the board but had taken to wearing a silver sun visor and sunglassed underneath a pair of goggles. He lost that game (probably because he couldn’t see properly!) and Korchnoi now needed only one more point to win the match. Fittingly, in game 18 (the second game in the viewer at the bottom of this post) Korchnoi deployed the French once more and Spassky tried the Advance Variation.

I was lucky enough to be sitting in the front row of the auditorium when this game was played and I can assure you the atmosphere was very tense indeed. Eventually Korchnoi overcame his opponent and when the formality of swapping and signing each other’s score sheets arrived I noticed Korchnoi turn his sheet over and scribble something on the back of it before passing it to Spassky. I saw that Boris took a look at the note and immediately turned pale with anger before leaving the stage humiliated.

Later on that evening, at a party held in honour of Korchnoi’s success, I got the opportunity to ask Viktor what he had written on that score sheet that had obviously distressed Spassky so deeply. Korchnoi chortled and said,

“Learn French idiot!”

I hope that this e-mail will go some way to redressing the inaccuracy of Kramnik’s statement which was in no way intentional on his part. How could he have known that this note of admonition was in fact a spur to drive Spassky’s opening studies and not his linguistic deficiency?

See you soon,

Cynthia